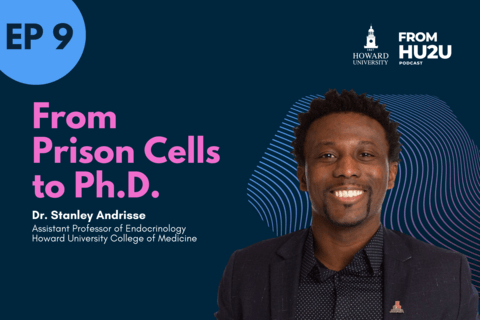

HU2U Podcast: From Prison Cells to Ph.D. feat. Dr. Stanley Andrisse

In This Episode

As a kid, we all make mistakes. For some reason, the consequences can be life-changing, for better or for worse. For Dr. Stanley Andrisse, his mistakes led him to three felony convictions where he faced a 20-year prison sentence. Dr. Stanley Andrisse is an endocrinologist, scientist, and professor at the Howard University College of Medicine. He joins host Frank Tramble today to chat about his incredible life pivot, dealing with grief and human emotion in prison, the power and privilege of being a Black doctor, and education as a form of therapy.

Host: Frank Tramble, former VP of Communications at Howard University

Guest: Dr. Stanley Andrisse

Listen on all major podcast platforms

Episode Transcript

From Prison Cells to Ph.D. feat. Dr. Stanley Andrisse

Publishing Date: Jan 16, 2024

[00:00:00] Frank: As a kid, we all make mistakes. For some reason, the consequences can be life-changing, for better or for worse. For Dr. Stanley Andrisse, his mistakes led him to three felony convictions where he faced a 20-year prison sentence. It was his father's battle with diabetes and his own intellectual curiosity that took him from one cell to another, the study of human cells, specifically endocrinology, the study of hormones. Let's dig into it.

Welcome to HU2U, the podcast where we bring today's important topics and stories from Howard University right to you. I'm Frank Tramble, today's host, and I'm here with Dr. Stanley Andrisse, endocrinologist, scientist, and professor at the Howard University College of Medicine. How you doing today?

[00:00:51] Stanley: I'm doing good. I'm here with you.

[00:00:53] Frank: All right. I appreciate that, I appreciate that. Well, welcome to the podcast. So, let's talk about the early days of Stanley. What happened that led to your convictions and, you know, your prison sentence?

[00:01:04] Stanley: Yeah, so, first, just thank you for the invitation to be on the show. So, growing up in Ferguson, Missouri, which a lot of people have become familiar with Ferguson through the events following The Killing of Mike Brown, and we've discovered and know the world knows from this report from the Department of Justice that there was this excessive use of force, over policing, and many other things that came to light from that report.

So, I grew up in that background of things, but I began making a number of poor decisions at, at a pretty young age. I was arrested for the first time at 15, so moved into the juvenile system at a young age. And even before being arrested for the first time, you know, I began selling drugs before I was even a teenager.

And if I take it back even before that introduction into the criminal legal system from those poor decisions, I can see that, you know, even in school, I can recall as early as elementary school

and middle school and even definitely in high school, I was suspended and I was in detention all the time. I was almost expelled from high school a number of times.

So, there was this belief of people that came from this area where I was at in North St. Louis, Ferguson area that there's really not much good that comes out of these types of areas. So, the officials, the politics, the teachers, the adults in the world of that little community and that had power and influence all thought that whatever came out of this place was, was bad.

So, even before my introduction into the criminal legal system, I had teachers, authorities, and the world telling this little, small part of our community that nothing good comes out of it. So, I mean, that's not to say that my decisions were, were my own decisions, but there's this whole social, cultural, political environment that is, is underplaying in places like Ferguson.

[00:03:12] Frank: Yeah, yeah. You know, I connect so much to your story. I'm originally from Detroit and from an area where, I mean, there was probably a 17% chance of me making it alive off of my street. And I had made some good decisions. I also made some really bad ones. And luckily, I didn't fall down that path.

But it wasn't until the death of my best friend that I really thought, "Okay, I got to make a change and there's a decision I got to make. I have to move forward to achieve the goals I want to, to get to where I want to be." What was the changing catalyst for you that led you from this path to being a doctor?

[00:03:45] Stanley: Yeah, so, I mean, as you mentioned in the introduction, you know, I'm a formerly incarcerated person with three felony convictions, was sentenced to 10 years in prison as a prior and persistent career criminal. I was sentenced under the three-strikes law of Missouri, meaning that I had three separate felony convictions. And, you know, the three-strikes law says that after three strikes, like in baseball, you're out. They push for a life sentence.

And so, I had a prosecutor pushing for a life sentence. My time range had changed from... I was looking at five to 15 years to looking at 10 years to life. And the prosecutor was pushing for life. And, you know, fast forward some time, also as you mentioned, I got sentenced to 10 years. You know, fast forward, I did my time, and I'm now a doctor.

Stan Andrisse, endocrinologist scientist, assistant professor at Howard University in the College of Medicine here, also some other affiliations as well along the path. But really what was the change for me was when I was incarcerated, or I guess I should even just talk a little bit about the, the sentencing.

So, during my sentencing, I had this prosecutor pushing for life and she felt that I needed that amount of time because I was this irreparable person, that I was unable to... you know, she felt that I was hopeless and, and didn't have the capacity to change. And so, she painted this picture of me as this dangerous threat to society in order to really push for this idea of sentencing me to life.

So, I have this person telling this young black male that they are this career criminal that is unrepairable. And, you know, I can recall when the judge came down with the 10-year sentence, it being, kind of, this out-of-body experience that, you know, it took me some time to get back into myself almost and just realize the moment.

And one of the first things that I asked the judge is if I could hug my mother, who, at this point in time, was in the back of the courtroom bawling in tears because she was losing her youngest son. So, I'm, I'm the youngest of five kids. My family we're immigrant family. We're Haitians. So, although we were in Ferguson, which is, you know, of course, a primarily black community, we felt very much like outsiders even in a black community.

So, we were, kind of, all we got. And so, to lose her youngest child, her youngest son, it was devastating. She was bawling in tears. And I asked the judge if I can go give her a hug. And the judge denied me the opportunity to go hug my crying mother. She ordered the bailiffs to come handcuff me, shackle my feet, and take me away.

And I, I, I say that because up until that point, I had been in and out of courtrooms quite frequently and I still had this belief that there was justice in the justice system. But, you know, I, I came to realize that there was justice for certain people and injustice for other people. And, you know, I came to realize that I was one of those people that the system didn't see as human, as a person, as deserving of respect and civility.

So, I, I went into prison very much feeling like this career criminal scum of the earth, irreparable person. And through much of my early sentence was feeling and moving in that way. You know, you asked what the change was. I was fortunate enough to have this mentor step into my life that saw a different trajectory. He saw me using my talents and potential differently, and he started investing in my potential.

That tied with, over the course of about two years during the course of my incarceration, my father went through a number of hospitalizations and surgeries and amputations where they literally started amputating piece by piece, starting with his toe, then his foot, then half his leg, then his whole leg, to the point that he ended up losing both his limbs and losing his battle with Type 2 diabetes.

So, during that process of, like, the emotional distress of losing my father, I read my first scientific article on diabetes while I was locked in this prison cell. And it would take me months to get through just one article for a number of different reasons. One being, for those listening that are familiar with scientific articles, every other word is something you've never heard of before.

And inside prison, you know, I don't have Google, WebMD, or Chat GPT to be looking things up so it would literally take me a long time to read through these. And I, you know, I share that with my students now. And I'm about to go into a journal club when I go back to my lab here today, and I asked them to read a paper in just one week. It would take me months to do it.

And what it actually enabled me, although my body was physically locked in this prison cell, my mind was freely roaming around the human cell. And, you know, as you opened up with that allowed me to, kind of, free myself from thinking of me as this career criminal. So, that was the beginning of the change.

It was this mentor coming into my life and really seeing me using the skills and talents that I had been using to sell drugs in the streets in a different way, and then me losing my father and diving into learning more about... as an endocrinologist, as you mentioned, I study hormones and particularly diabetes and insulin, and it was in this prison cell that I developed that passion.

[00:09:16] Frank: That's such a, such a great story of overcoming and still pushing forward. Was the, you know, the study of diabetes, and then particularly, endocrinology, did you choose that mainly because of your father?

[00:09:28] Stanley: Yeah. So, when I was in prison, I started reading about it more so as to deal with the emotional distress of losing him. I had no idea that it would lead me to a career. So, I, I often share that in prison, one of the reasons that the environment is such a volatile and hostile environment is that, you know, life is happening and things like people are dying on the outside, people are losing their significant other, their children are getting sick and parents are getting sick.

And that emotional distress, when we think about the stages of grief and how us as humans go through grief, there are things such as feeling sad and depressed that might lead to crying. In prison, you are not afforded that human feeling of feeling sad and leading to tears. That could literally bring harm your way. Another aspect of grief is feeling angry and, you know, yelling or hitting your fist against a desk.

Showing that type of anger, again, could literally bring harm your way. So, what I experienced on the inside was that people didn't have the ability to be human. They actually had to bottle up these normal human emotions, and it resulted in explosions. So, people would be bottling all this up and then eventually, it would explode and there would be volatility and hostility that comes out.

And then it's viewed as this person is just a bad person or a violent person, whereas the underlying emotional distress is not being addressed. So, for me, I was reading these articles as an outlet to get these emotions that I was not allowed to have out.

So, my love for endocrinology came really out of just trying to emotionally grieve the loss of my father. It wasn't until later in my period of incarceration where I had this mentor constantly in my ear like, "You should continue your education. You're so bright." And so, it wasn't until later that I saw it as a possibility.

[00:11:31] Frank: So, what are some of the messages you try to share with your students around either your story or attached to why, you know, they should be also learning not only from you, but the particular science that you are an expert in?

[00:11:45] Stanley: So, some of the messages in terms of the social justice work that I do, or...

[00:11:50] Frank: Yeah, mm-hmm.

[00:11:51] Stanley: One of the things that I often share is that we must understand where we came from to understand where we're going. I'm at the College of Medicine, so my students are training to become medical doctors. Because they are training to become medical doctors and because we are Howard University, so I'm primarily training people of color and people who are underrepresented in medicine, because of that fact, the credential of medical doctor gives you certain privileges in this world.

Like, when someone with those types of credentials speak, their words are heard a little bit different than, than others. I mean, that's just one of the privileges of that type of degree. And then you add that the person is a person of color with that degree. Like, they actually have a great deal of power they can bring to our communities. So, I often share with them, they need to realize this privilege that they're gaining through their training, and they need to use that privilege.

And in order to properly use that privilege, again to the quote that I just often share, is that we must understand where we came from to understand where we're going. So, even though you're studying to be a medical doctor, you need to study what has happened to our people in this country and across the world really, and you need to become a student of understanding the disparities that have been faced by black people in this country and in the world.

So, you know, the message that I often share is that, "Understand your privilege and power that your training will give you, and then understand how you can use that to make change." And in learning about the past, I've experienced it here at Howard where I really think that, particularly, like, in the medical school and, and... or I should say particularly in places where you're training, what brought you to this position didn't require you to be a social justice guru, right?

[00:13:51] Frank: Mm-hmm.

[00:13:51] Stanley: So, we have, for instance, people in certain positions, even at a place like Howard University, that are not social justice conscious as much as you would think, even though we're here at The Mecca. And so, they're here because they're expert cardiologists, expert surgeons, whatever it may be.

But what I found is that some folks here don't really understand what Howard was founded on in terms of, you know, we were founded to train and educate former slaves. And to that same respect, I think we need to understand that, that being part of our history, Michelle Alexander has, kind of, detailed it very well in this transition of how mass incarceration has transitioned into the new Jim Crow and a result of manifestation of slavery.

So, in that respect, we need to understand at Howard, we should be doing all that we can to educate, train, and support people who have been impacted by the system. So, I mean, I, I'm constantly just sharing with my students the idea of, "You can't just focus on being a medical doctor because you're too much to the world. You have to understand the history of what happened to us in this country and in the world."

[00:15:12] Frank: Yeah, and I, I love that that's the context that you bring to the medical education because I think that's what's unique about not only you but Howard. You know, let's, let's talk a little bit about the, the moment. You've said you've been here for six years, right?

What does it feel like and mean to you to be teaching and have gone through everything that you've gone through and now, you know, a medical professional, professor, an expert in this space here at Howard University?

[00:15:37] Stanley: It means the world to me, to be honest. I'm coming from Johns Hopkins, is where I was previous to here, so I was about five years at Johns Hopkins as a postdoc fellow in endocrinology and then moving into an adjunct faculty role there. And I just got some grant funding there and I was looking at the academic ladder there.

But when this opportunity presented itself, it was, it was, kind of, a no-brainer because being here at, what I call, The Mecca, and what I actually... I prefer to even go a step further from Ta-Nehisi Coates's Mecca analogy, I feel like it's Wakanda. I can recall, for instance, I moved up and I got some funding at Johns Hopkins to move into this adjunct faculty role and potentially climb the ladder there, and it was through a lot of advocacy work.

And I was kicking down doors and demanding meetings with the presidents and provosts and deans and asking for change. And we developed this fellowship to give funds to help black and brown scientists and physicians transition into faculty. And I got the funds. And I could just recall, as I was kicking down doors and demanding these meetings, I'd walk into these rooms.

There's one particular room at Johns Hopkins. It's this giant boardroom with this, like, fancy Italian wood, and everything in there is just fancy. And you walk into the room, and along all the walls are bunch of old white people looking down at you in these photos. And then I sit at the table and there's a bunch of primarily old white men sitting at me and looking at me at the table as I'm pushing for change.

And I could just remember my first time meeting with Provost Wutoh, and I was meeting with him with Dr. Muhammad, and he had several other people in the room. We were talking about prison education and how we need to be continuing the history of Howard to educate... you know, we, we were founded on educating former slaves, as I was mentioning, and I think the continuation of that is to help educate people who are previously incarcerated.

We were having that conversation with them, and I walk into the room. It was, again, one of these rooms where it was this big boardroom with a fancy table, and I look on the walls, and what I see down is black people looking at me. Then I look around the table and I see a bunch of, like, educated black individuals in suits and I was just like... I, I'm trying to keep my cool to get my message to Provost Wutoh, but in my head, I'm like, "Where did I just walk into?"

Like, "This literally feels like a scene out of Waka... like, out of Black Panther, like we just walked into Wakanda." Like, I've never walked into a room that was of that type of status, right? With nothing but black people looking at me. And that's something that is very special to me in, in terms of me being here.

And I, I think, you know, just every day, I'm, I'm about to go back to my lab. We're, we're just starting up some more research, and I'm going to walk into a lab with a bunch of folks in white lab coats that look like me and that are my students that I'm training. And I, I think... I mean, that feeling is just... every day, it's fantastic.

[00:18:48] Frank: Yeah, I mean, I, I think that's something we all share when we walk the, the halls and, and the work that we do. It's just such a unique and beautiful space to, to, to really thrive. You talked a little bit about your social justice initiatives. I know you have a nonprofit. Why don't you tell us a little bit about what that nonprofit is and what your focus is?

[00:19:07] Stanley: Yeah, I appreciate you for mentioning that. So, through my journey... and I, I was sharing a little bit of this before we got on air, but through my journey, I have a, a beautiful wife. I have a four-year-old daughter who is amazing. I love seeing her grow. I have a one-and-a-half year old son who is just, just an incredible joy to be around us. His love for life is just amazing.

And I could easily just say I, I'm here, like, I'm at The Mecca, I'm at Wakanda, I got a beautiful family. Why do I need to be doing and putting so much energy to this social justice work? And, you know, as I was mentioning before we got on air, I couldn't sleep if I wasn't doing this work.

I really couldn't see myself not trying to give back to others who have experienced the experiences that I had, such as growing up in places like the Ferguson area and such as going through incarceration to now being where I am at Howard.

You know, the organization, the nonprofit that I founded, was essentially this idea around how do we create a playbook to help individuals get through those hurdles, barriers, and roadblocks that are put up for people who are formerly incarcerated. So, it was co-founded by myself and two other people I was incarcerated with.

And I can recall, you know, as I was going through this change when I was incarcerated, I would be walking around the track with one of the co-founders who wasn't quite there yet on the idea, and I had moved to this point where I was telling him, "You know, I'm going to get out and I'm going to be a doctor, man." Like, and he's looking at me like, "What? Do you see where the..." Like, "Do you see where we're at?"

At that particular time, I was at, you know, this level four prison, which is a maximum type of security prison, and it was a dismal place. And to have that type of aspiration just seemed crazy to him. And, you know, time went on and then I, I got out and I started pushing in that direction.

He saw, and I, I saw the transformative power of education. When, when I tell people, you know, that word gets thrown around a lot, how education is transformational, but for me, what it was, I got out of prison and there was just a lot of trauma that I didn't realize that I needed healing from.

And education was not only transformational, but it was therapeutic and helping me heal through some of the things that I had been through, where just diving into education and expanding your mind in that way and diving into whatever the material is that you're studying is literally this form of therapy for people that have been through that type of trauma, in that it can help elevate your mind to this different thinking.

Because the traumas of incarceration lead you to believe that you can't bring value to this world, that you can't bring value to yourself, that your, your self-worth is diminished. And education helps repair some of those things and those beliefs. So, it was literally this therapeutic healing thing. And so, when I discovered that, I told one of the co-founders, who was still incarcerated, I was like, "Education is so powerful."

You know, when he got out, I encouraged him and helped him to use education to change his life and perspective. And then we started doing that for a couple other people we were incarcerated with. And then, you know, it was at that point where we were like, "This is really something..." like, "We really have a hold of something."

This idea of providing a supportive community and resources and mentoring to folks to use education as this transformative tool, we ended up founding the organization, which is called From Prison Cells to PhD. And it was more so part of my journey, but the idea is more of a metaphor of going from this place of feeling a sense of hopelessness and despair to moving to a place of feeling a sense of hope, self-value, and self-worth.

And we saw education as the vehicle. Education is not a degree. It's not the end all, be all. What we saw it as is a vehicle to get from A to B as someone is transitioning back into the community. So, we started the organization. It's actually in its sixth year, which is, you know, the same amount of time I've been here at Howard.

And we've now helped thousands of individuals across the country. We have a footprint in over 35 states. We've have over 300 people that have graduated through the programming we do. We have a policy division. We have a research division that's funded by Bill & Melinda Gates.

We have funding from the National Institutes of Health, from the National Science Foundation. We have over 30 people that are employed by the organization. 85% of them are formerly incarcerated individuals. So, it's really just great to see the growth and impact that it's made in the community.

[00:23:54] Frank: Absolutely, absolutely amazing. And I love that one of the things you and I spoke about is the fact that when we get into these positions and we've gone through obstacles, it's almost our responsibility to turn back and make sure that the, the people who may not have an opportunity or didn't even see the light that we saw, that we step in.

And I think you talked about the fact that it was a mentor that helped you. And there was a mentor that helped me, too. And I think we sometimes forget about the power of what one good mentor can do to just change the possibilities of what you believe your life can be.

So, for the student who may be listening, or the parent that may be listening of a young individual who, you know, may be going down the wrong path and may face, you know, as the tale say of the face of two paths in the woods, what do you want to tell them about what can help inspire them to move in the right direction?

[00:24:45] Stanley: Yeah, that's a great question and I get asked that often. I mean, I am blessed, fortunate, privileged to be able to speak to a lot of different people across the country and even in several different countries about this particular topic. So, I get asked that a lot, and I really lean on the message that my father gave me.

And, and so, I mentioned I ended up losing my father to his battle with Type 2 diabetes before I was able to, kind of, realize this message that he was telling me. That message is, he used to tell me this phrase, "Il n'est janm pa twò ta pou fè bien," which is French creole. So, I mentioned that my family is Haitian and my first language growing up was creole. And so, he would tell me that phrase, which translates to, "It is never too late to do good."

And that phrase is actually the subtitle of my book. So, I, I recently released a book, From Prison Cells to PhD: It is Never Too Late to Do Good. It was a number one new release on Amazon educator biographies. He would tell me this multiple times throughout my childhood and into my adolescence and as I was making all these poor decisions. And then, you know, I ended up, kind of, losing ties with him and then going away to prison and then losing him.

And the message that he was delivering, it's sometimes translating between languages. There's not an exact translation, so the exact wording is, "It's never too late to do good," but the meaning that he was pushing for is that, "It's never too late to reach your full potential and it's never too late to do the right thing."

And, you know, when I think about growing up in Ferguson and the challenges of that particular area, I think about that my family grew up in Haiti and Port-au-Prince and the challenges of that area. And so, my dad was not unfamiliar to challenges and the way challenges can make you... you know, push you in directions of making poor decisions. So, he understood that in humans, we make poor decisions.

But what he was telling me is that, "Although I see you making these poor decisions, I believe in your ability to change. And I believe that one day, you will see your ability to change, and you will see the value you can bring to yourself and others." And it took me a long time to hold onto that message, but it's such a powerful message to the criminal legal system and to youth and to parents, actually.

So, your question was, what would I tell a parent? And I would tell them it's never too late to do good. I would, I would ask them to understand what that truly means. I would ask them to have patience and compassion. So, although your child may be making poor decisions at this moment, have that faith and that patience and that belief that they have as human beings.

You know, we are not static creatures. We are dynamic and we are constantly changing. The world is constantly changing. So, provide the support, provide the love, provide the compassion, and provide the space for the person to develop into who our Creator intends for them to be.

[00:27:48] Frank: Yeah, wonderful, wonderful. Well, you heard it here. It's never too late to do good. And at Howard University, this will continue to be a place that helps us realize our full potentials, and to be places where you see we have some of the most elite and best faculty in the country that care not just about the education of your student, but the growth of who they are as people.

Thank you so much for joining the podcast today. I appreciate you. This is HU2U, the podcast where we bring today's important topics and stories from Howard University right to you. I'm Frank Tramble, today's host, and thank you for listening. HU! You know!